"What do lesbians do? I mean, sexually?” the woman asked me. Even though I’d been working for months with a couple of friends to create a safe space for LGBTQ youth to talk about faith, I was not prepared for her question. Lesbian sexual practices weren’t something I’d spent much time or energy thinking about as a twentysomething gay man.

The questioner and I were at a crowded reception at a youth ministry conference. She’d been in the workshop I’d just finished teaching about the creation of The Naming Project, a ministry to meet the spiritual needs of LGBTQ youth. “I’m mentoring a girl at my church,” she continued, “and she’s starting to share a little bit with me about her self-discovery. It’s great that she feels that she can trust me, but she’s asking me questions that I don’t know how to answer. I was hoping you could educate me.”

I also looked around, suddenly aware that if overheard, my honest answer might cause some consternation at this youth ministry conference.

In my discomfort, I almost cracked a joke. But I realized that I was standing before a very well-intentioned, straight, cisgender woman who wanted to be a good adult mentor for a young child of God who had some real questions about what she was “supposed” to do or what was “OK” to do. She’d just met me, but this woman had worked up the courage to ask me a serious question. She deserved a serious response.

Her question took me back to an earlier time before we had ever conceived of The Naming Project. In a panel discussion about the faith needs of LGBTQ youth, a youth minister in the audience shared that she felt completely unprepared for what to do if one of the youth at her church came out to her: “I want to be supportive and helpful, but I don’t know what the right thing to do is. I’m scared I’ll say nothing, or at least nothing helpful, and then the youth will think I’m not supportive, and I am, but I don’t know how to be.”

This youth minister had been a friend of mine for years. She had been supportive of my coming out and my identity as an openly gay Christian. I (and others in her life) had taught her something about being an LGBTQ person who keeps his faith, and now youth were looking to her to teach them about the relationship between Christianity and LGBTQ people.

Her question made me aware of how much the church’s erasure, rejection, and lack of understanding were going to hurt youth. Both of these women were identifying where the church has historically fallen short even without always being explicitly anti-LGBTQ. Such questions are learning opportunities for the church—if the institution is willing to do that work.

There are many people in the church who intend to listen, learn, and work, but the everyday demands of ministry often negate those good intentions. Rather than recognize LGBTQ youth as unique creatures with unique needs, such persons erase sexual orientation or gender identity, burying it in a culture of assumed heterosexuality and cisgender identity (the notion that one’s internal sense of gender matches the way they are perceived externally). Or if well-meaning church folks do validate LGBTQ sexual orientations and gender identities, those sexual orientations and gender identities are considered something separate from the person’s growing faith identity.

Unintentionally or not, erasing LGBTQ youth or treating their sexual orientation or gender identity as completely separate from their faith leaves LGBTQ youth with no community in which to integrate their faith, sexual orientation, and gender identity. In a perfect world, every community is one in which all aspects of identity can be explored. But historically, we pick apart a person’s identity, treating its various aspects as separate and occasionally competing.

Fielding questions about LGBTQ youth and faith has become pretty routine in the time I’ve been running The Naming Project. Over the past fifteen years, my fellow creators and leaders of this youth ministry have been asked many times “how best to” accommodate LGBTQ youth, decide on sleeping arrangements, use language and terminology, find trusted local resources, and so on.

Most of the questions are from straight, cisgender pastors and youth ministers, like the two women who lobbed questions at me on different occasions. Such persons are loving and want to be affirming, but they haven’t been involved in the LGBTQ community and may be unfamiliar with the language and terminology that LGBTQ youth use to describe themselves. They are often scared that even the wording of their question might offend me. And some feel shame for not already knowing the answer.

Most of the time, pastors and youth ministers fall into one of two categories: either they want answers to quick, logistical questions—such as about updating their existing church policies or figuring out sleeping arrangements on a trip—or they describe elaborate scenarios and end with “Any advice on what we should do?”

Common examples of such questions include the following:

-

Can you share with us thoughts or resources you have for a youth ministry geared to LGBTQ or confused/transitioning teens and youth to come and worship free of judgment or fear of someone trying to “fix” them? We feel that it is a need that has not been met in our state and that it is a large one.

-

Our church is looking for ways to reach out to LGBTQ high school students, particularly those who fear that their churches or families will never accept them for who they We know there’s a great need, but we don’t have a clear idea to what kind of programming youth will respond best. How did you initially draw up your program, and how has it evolved? Do you carry most of the leadership, or do you bring in resource people from farther away? Do you have any background material on your programs that you could send us?

-

What kind of praise have you received from parents and congregations? Likewise, what kind of backlash?

-

When starting your ministry, what resources did you already have, and what did you need to get in order to get the program off the ground?

-

How do you handle sleeping accommodations during camps and trips with LGBTQ youth?

-

A high school teacher in our congregation asked me if I had any suggestions for how she might help a student whose father is a less-affirming pastor. The student told her teacher that she thinks her family would disown her if she came out as She lives in a very small town, so any local/regional resources might be difficult for her to access in a way that feels safe for her. I am wondering if you could recommend particular online support groups / safe spaces for this student.

As the first and largest LGBTQ Christian youth ministry program in the United States, The Naming Project has had to think through these questions. People write to us because they believe they can learn from our experience.

The Naming Project started with a question and a plea for help from a woman I considered a mentor. My first job out of college was providing logistical and planning support for a youth and family ministry institute. One of the executives at the organization was a woman named Marilyn Sharpe. She was a confirmation and parenting guru, having led both a youth confirmation group and a support group for mothers at a huge area church for decades. She had an adult lesbian daughter who had already opened Marilyn’s eyes to the realities of LGBTQ people. Marilyn was vocally supportive, making sure I knew that I was welcome and supported in my work at the youth and family ministry institute.

One day, Marilyn came by my desk with a request for help. A friend at her church, the wife of one of the pastors, had approached Marilyn with a question about a fifteen-year-old son who had come out to his parents. The parents were accepting, and they wanted to find him a community where he could be around peers who were also growing up and coming out.

The family tried attending a local LGBTQ youth center, but it wasn’t a good cultural fit for the son. The youth at the center had been on the receiving end of discrimination and even abuse. Some were forbidden to speak about being LGBTQ at home. Some had been kicked out of their homes. They were couch surfing or, in some cases, living on the street, doing whatever they needed to do to survive. Many saw the church as the source of their troubles, and they had no interest in engaging with any kind of church ministry, even if it was affirming. Sometimes such youth and families seeking local resources will find a caring environment in which the youth can explore their sexual identity in a caring group of peers and guiding adults. Most often, these environments are secular. Their leaders are not equipped to explore spirituality issues. In many cases, the adults leading the programs have their own baggage around faith and their involvement with faith communities. They feel that exploring spirituality is a role for individual faith communities, not the group they lead.

The boy in question was a suburban teenager with two parents who continued to accept, love, and support him. In so many ways, he was blessed and privileged. The family was shocked to discover that other youth often aren’t accepted and the extremes to which they have to go to survive. The reality is that 40 percent of the homeless youth population identifies as LGBTQ despite being less than 10 percent of the total youth population. Nearly 90 percent of homeless LGBTQ youth are homeless specifically because they are LGBTQ.

The family didn’t realize how much they were bucking a trend by trying to support their son. Their eyes had been opened to the reality of many LGBTQ youth, but they were no closer to finding their son peers who would help and support him in coming out and living out his values as a Christian.

They tried LGBTQ-focused and LGBTQ-friendly churches, but the congregations seemed to be filled with adults. If there were youth, they were the children of LGBTQ parents and often were much younger and straight. There were no out youth in any of the congregations. The other churches were either hostile about or silent on LGBTQ issues.

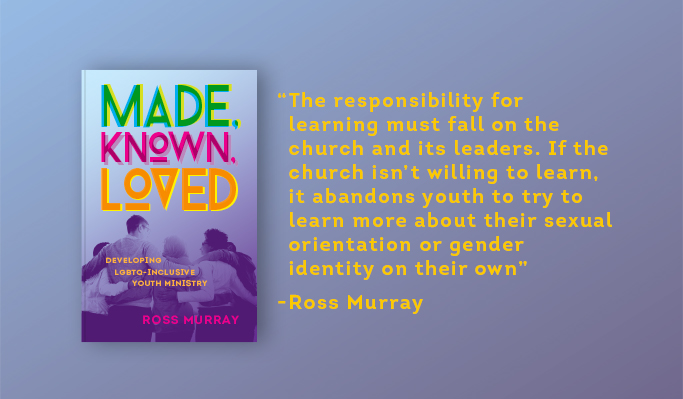

The responsibility for learning must fall on the church and its leaders. If the church isn’t willing to learn, it abandons youth to try to learn more about their sexual orientation or gender identity on their own, with little control of the quality of information they are receiving. Where youth go for information and guidance can often lead them on a dangerous path of half-truths, misinformation, and even exploitation. If they search online to explore their sexual orientation or gender identity, LGBTQ youth will often land with harmful people and in unsafe situations.

In short, if churches are too squeamish to talk about sexuality with youth, youth go elsewhere to develop their identities as sexual beings. Since LGBTQ youth are not a part of mainstream culture, they have to find special environments to explore their sexuality. Those environments either are often destructive or at least lack the spiritual foundation of churches. In the least-bad scenario, these youth develop spiritual and sexual identities that are miles apart. In the worst situations, LGBTQ youth deny one or another part of their identity.

One day, the aforementioned concerned mother came home from work to find a forty-year-old man waiting on her doorstep. In looking for a community that could support and inform him as a gay boy, the son had found online chat rooms and community groups. He connected and conversed with an older man. Through the chat, the youth had provided enough information for the man to find his house, and the man was paying him a visit.

The mother was rightly alarmed at a stranger being at her house to visit her son. It prompted her to reach out more urgently to everyone she knew, asking for church-based LGBTQ youth groups. The question had come to Marilyn, and Marilyn was now presenting it to me. Marilyn also brought the same story and question to my friend and colleague Jay Wiesner. We told her we didn’t know of any such groups but that we’d look into it.

There are organizations within every Christian denomination actively working to help integrate faith identity, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Originally created in the 1970s to provide safe places for LGBTQ people to worship without the fear of being outed and losing their church, family, or jobs, these organizations evolved into advocates for LGBTQ-inclusive policies in denominations. ReconcilingWorks, More Light Presbyterians, Dignity (Catholic), Integrity (Episcopalian), and countless other LGBTQ denominational groups have been working for a number of years to address faith and sexuality in a substantial and holistic way.

When Jay and I looked closer, we found that many of these advocacy groups did not include youth as a part of their mission. For example, when I was first getting involved with the Lutheran group ReconcilingWorks in the early 2000s, the organization had a policy of not engaging with anyone under eighteen years old. The perception that LGBTQ folks are predatory or dangerous to young people had kept these faithful LGBTQ adults from mentoring or sharing their faith with younger LGBTQ Christians. These faithful adults did not want to be accused of “recruiting” youth into a “homosexual lifestyle.” They knew that even an unfounded accusation would ruin the reputation of their group.

The organizations for LGBTQ youth didn’t address religion. The religious youth groups didn’t address LGBTQ issues. And the religious organizations that addressed both LGBTQ issues and religion excluded youth. It was as if of the three—religion, youth, and LGBTQ issues—any group could only address two at once.

The Open and Affirming Coalition of the United Church of Christ was an exception. The organization employed a staff member to deal with youth and young adult issues and had compiled a bibliography of resources for pastors, youth, and families. A couple of people mentioned rumors of a Jewish LGBTQ youth program, but we never did manage to find evidence of its existence. These organizations and their programs were designed by and for baby boomers (the first generation to be bold enough to come out at all). They often don’t connect with the current situation of youth who live in a very different context.

Jay and I sat down with Marilyn in our office and reported our findings—or lack of findings. After sharing that we couldn’t find any active LGBTQ youth groups for this family, we looked at each other and said, “Well, we’ll need to create something.”

Marilyn told me later she nearly burst into tears at our spontaneous decision to create an LGBTQ youth ministry that hadn’t existed until that point.

But now that we had said it, we had to figure out how to do it! And that came with its own set of challenges. Empowered by Marilyn’s questions and her support for this new ministry, we set about developing what an LGBTQ youth ministry might look like.

This is an excerpt from the introduction of Made, Known, Loved: Developing LGBTQ-Inclusive Youth Ministry.

Learn more about The Naming Project here.